(Triple only) Titration calculations – videos

Here are a couple of videos explaining how to perform titration calculations:

Here are a couple of videos explaining how to perform titration calculations:

| Salt | Solubility | Exceptions |

|---|---|---|

| sodium (Na+), potassium (K+) and ammonium (NH4+) | soluble | none |

| nitrates (NO3-) | soluble | none |

| chlorides (Cl-) | soluble | silver chloride (AgCl) and lead (II) chloride (PbCl2) |

| sulfates (SO42-) | soluble | barium sulfate (BaSO4), calcium sulfate (CaSO4) and lead (II) sulfate (PbSO4) |

| carbonates (CO32-) | insoluble | sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), potassium carbonate (K2CO3) and ammonium carbonate ((NH4)2CO3) |

| hydroxides (OH-) | insoluble | sodium hydroxide (NaOH), potassium hydroxide (KOH) and calcium hydroxide (Ca(OH)2) (calcium hydroxide is slightly soluble) |

An acid is a proton (H⁺) donor.

A base is a proton (H⁺) acceptor.

A proton is the same as a hydrogen ion. A good way to think about that is to realise that a hydrogen atom is just one proton and zero neutrons surrounded by only one electron. If that atom becomes an ion by the removal of the electron, then only one proton is left.

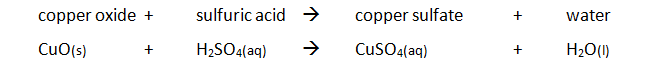

When sulfuric acid reacts with copper (II) oxide (CuO):

Cu²⁺O²⁻ (s) + H₂SO₄ (aq) → Cu²⁺ (aq) + SO₄²⁻ (aq) + H₂O (l)

H₂SO₄ is an acid. It donates protons (H⁺) to CuO, the base.

An acid is a proton donor.

A base is a proton acceptor.

A proton is the same as a hydrogen ion. A good way to think about that is to realise that a hydrogen atom is just one proton and zero neutrons surrounded by only one electron. If that atom becomes an ion by the removal of the electron, then only one proton is left.

Acid reactions summary

alkali + acid → water + salt

base + acid → water + salt

carbonate + acid → water + salt + carbon dioxide

metal + acid → salt + hydrogen

To assist remembering this list, many pupils find it useful to remember this horrid looking but very effective mnemonic:

AAWS

BAWS

CAWS CoD

MASH

Acids are a source of hydrogen ions (H⁺) when in solution. When the hydrogen in an acid is replaced by a metal, the compound is called a salt. The name of the salt depends on the acid used. For example if sulfuric acid is used then a sulfate salt will be formed.

| Parent acid | Formula | Salt | Formula ion |

|---|---|---|---|

| sulfuric acid | H2SO4 | sulfate | SO42- |

| hydrochloric acid | HCl | chloride | Cl- |

| nitric acid | HNO3 | nitrate | NO3- |

Acid + Alkali and Acid + Base

A base is a substance that can neutralise an acid, forming a salt and water only.

Alkalis are soluble bases. When they react with acids, a salt and water is formed. The salt formed is often as a colourless solution. Alkalis are a source of hydroxide ions (OH⁻) when in solution.

alkali + acid → water + salt

base + acid → water + salt

Examples of acid + alkali reactions:

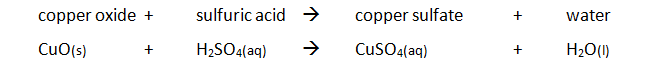

Example of an acid + base reaction:

CuO (s) + H₂SO₄ (aq) → CuSO₄ (aq) + H₂O (l)

Acid + Carbonate

carbonate + acid → water + salt + carbon dioxide

A carbonate is a compound made up of metal ions and carbonate ions. Examples of metal carbonates are sodium carbonate, copper carbonate and magnesium carbonate.

When carbonates react with acids, bubbling is observed which is the carbon dioxide being produced. If the acid is in excess the carbonate will disappear.

Examples of acid + carbonate reactions:

Acid + Metal

metal + acid → salt + hydrogen

Metals will react with an acid if the metal is above hydrogen in the reactivity series.

When metals react with acids, bubbling is observed which is the hydrogen being produced. If the acid is in excess the metal will disappear.

Examples of acid + metal reactions:

Underneath are 3 acid reactions :

alkali + acid → water + salt

base + acid → water + salt

carbonate + acid → water + salt + carbon dioxide

A base is a substance that neutralises an acid by combining with the hydrogen ions in them to produce water.

A base usually means a metal oxide, a metal hydroxide or ammonia.

Alkalis are bases which are soluble in water.

Some metal oxides are soluble in water and react with it to form solutions of metal hydroxides. For example:

Na₂O (s) + H₂O (l) → 2NaOH (aq)

Apart from this and other group 1 oxides (such as potassium oxide) most other metal oxides are not soluble in water.

One exception is calcium oxide which does dissolve slightly in water to form calcium hydroxide (known as limewater):

CaO (s) + H₂O (l) → Ca(OH)₂ (aq)

Ammonia is another base. Ammonia reacts with water to form ammonium ions and hydroxide ions:

NH₃ (aq) + H₂O (l) ⇋ NH₄⁺ (aq) + OH⁻ (aq)

All the solutions produced here contain hydroxide ions (OH⁻) so they are all alkalis.

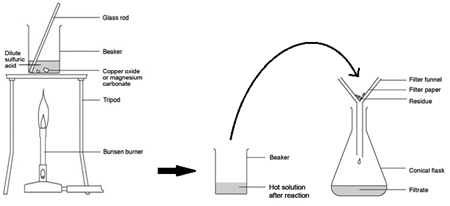

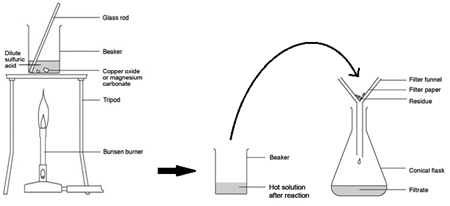

Excess Solid Method:

Preparing pure dry crystals of copper sulfate (CuSO4) from copper oxide (CuO) and sulfuric acid (H2SO4)

| Step | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Heat acid (H2SO4) in a beaker | Speeds up the rate of reaction |

| Add base (CuO) until in excess (no more copper oxide dissolves) and stir with glass rod | Neutralises all the acid |

| Filter the mixture using filter paper and funnel | Removes any excess copper oxide |

| Gently heat the filtered solution (CuSO4) | To evaporate some of the water |

| until crystals form on a glass rod | Shows a hot saturated solution formed |

| Allow the solution to cool so that hydrated crystals form | Copper sulfate less soluble in cold solution |

| Remove the crystals by filtration | Removes crystals |

| Dry by leaving in a warm place | Evaporates the water |

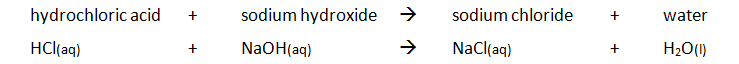

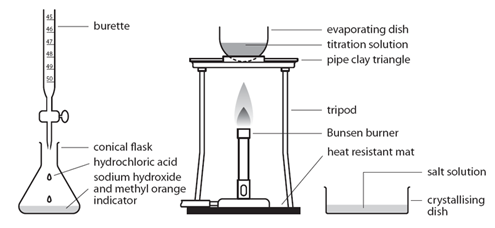

Titration Method:

Preparing pure dry crystals of sodium chloride (NaCl) from hydrochloric acid (HCl) and sodium hydroxide (NaOH)

Before the salt preparation is carried out using the below method, the volume of acid that exactly reacts with 25cm3 of the alkali is found by titration using methyl orange indicator.

| Step | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Pipette 25cm3 of alkali (NaOH) into a conical flask | Accurately measures the alkali (NaOH) |

| Do not add indicator | Prevents contamination of the pure crystals with indicator |

| Using the titration values, titrate the known volume acid (HCl) into conical flask containing alkali | Exactly neutralises all of the alkali (NaOH) |

| Transfer to an evaporating basin & heat the solution | Forms a hot saturated solution (NaCl(aq)) |

| Allow the solution to cool so that hydrated crystals form | Sodium chloride is less soluble in cold water |

| Remove the crystals by filtration and wash with distilled water | Removes any impurities |

| Dry by leaving in a warm place | Evaporates the water |

(Note – This process could be reversed with the acid in the pipette and the alkali in the burette)

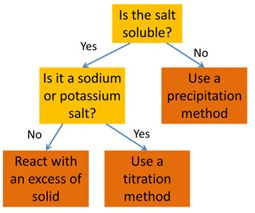

How to select the right method for preparing a salt:

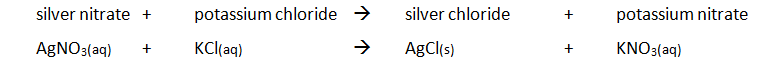

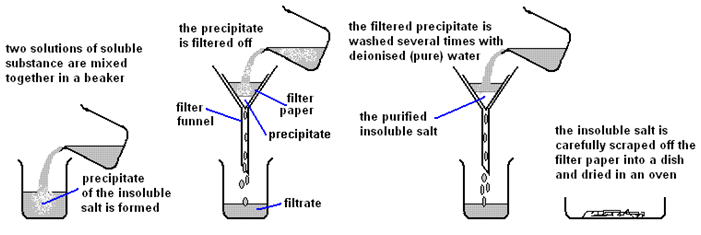

Precipitation Method:

Preparing pure dry crystals of silver chloride (AgCl) from silver nitrate solution (AgNO3) and potassium chloride solution (KCl)

| Step | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Mix the two salt solutions together in a beaker | Forms a precipitate of an insoluble salt (AgCl) |

| Stir with glass rod | Make sure all reactants have reacted |

| Filter using filter paper and funnel | Collect the precipitate (AgCl) |

| Wash with distilled water | Removes any the other soluble salts (KNO3) |

| Dry by leaving in a warm place | Evaporates the water |

Excess Solid Method:

Preparing pure dry crystals of copper sulfate (CuSO4) from copper oxide (CuO) and sulfuric acid (H2SO4)

| Step | Explanation |

|---|---|

| Heat acid (H2SO4) in a beaker | Speeds up the rate of reaction |

| Add base (CuO) until in excess (no more copper oxide dissolves) and stir with glass rod | Neutralises all the acid |

| Filter the mixture using filter paper and funnel | Removes any excess copper oxide |

| Gently heat the filtered solution (CuSO4) | To evaporate some of the water |

| until crystals form on a glass rod | Shows a hot saturated solution formed |

| Allow the solution to cool so that hydrated crystals form | Copper sulfate less soluble in cold solution |

| Remove the crystals by filtration | Removes crystals |

| Dry by leaving in a warm place | Evaporates the water |

Objective: prepare a pure, dry sample of lead (II) sulfate (PbSO₄).

Preparing a pure, dry sample of lead (II) sulfate (PbSO₄) from lead (II) nitrate solution (Pb(NO₃)₂) and sodium sulfate solution (Na₂SO₄).

Pb(NO₃)₂ (aq) + Na₂SO₄ (aq) → PbSO₄ (s) + 2NaNO₃ (aq)

Test for hydrogen gas (H2)

Test for carbon dioxide (CO2)

Tests for gases

| Gas | Test | Result if gas present |

|---|---|---|

| hydrogen (H2) | Use a lit splint | Gas pops |

| oxygen (O2) | Use a glowing splint | Glowing splint relights |

| carbon dioxide (CO2) | Bubble the gas through limewater | Limewater turns cloudy |

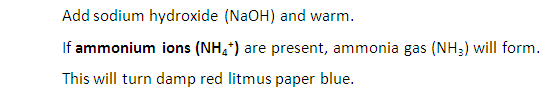

| ammonia (NH3) | Use red litmus paper | Turns damp red litmus paper blue |

| chlorine (Cl2) | Use damp litmus paper | Turns damp litmus paper white (bleaches) |

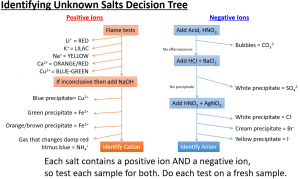

A flame test is used to show the presence of certain metal ions (cations) in a compound.

Properties of the platinum or nichrome wire is:

When put into a roaring bunsen burner flame on a nichrome wire, compounds containing certain cations will give specific colours as follows.

| Ion | Colour in flame test |

|---|---|

| lithium (Li⁺) | red |

| sodium (Na⁺) | yellow |

| potassium (K⁺) | lilac |

| calcium (Ca²⁺) | orange-red |

| copper (II) (Cu²⁺) | blue-green |

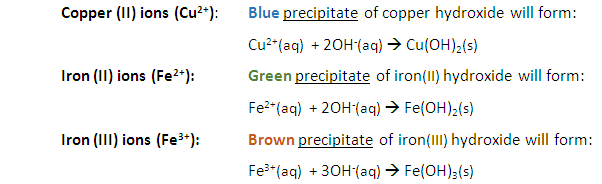

Describe tests for the cations Cu2+, Fe2+ and Fe3+, using sodium hydroxide solution

First, add sodium hydroxide (NaOH), then observe the colour:

Underneath is Sodium Hydroxide added to:

Iron (II) Ions

Iron (III) Ions

Copper (II) Ions

Ammonia

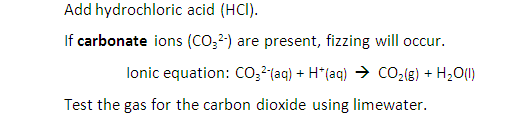

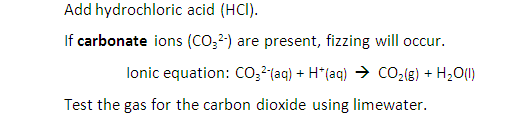

Describe tests for anions: Carbonate ions (CO32-)

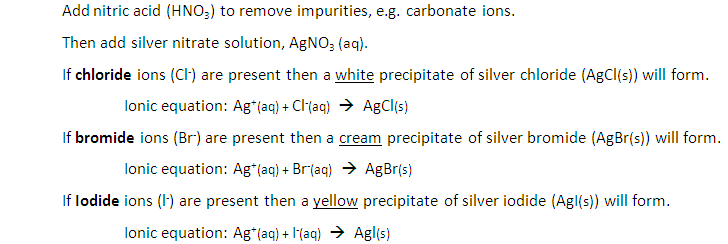

Describe tests for anions: Halide ions (Cl–, Br– and I–)

Underneath are the tests for:

chloride ion test, bromide ion test, iodide ion test, sulfate ion test, carbonate ion test

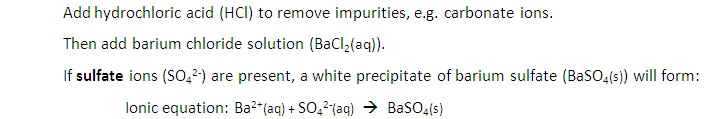

Describe tests for anions: Sulfate ions (SO42–)

Describe tests for anions: Carbonate ions (CO32-)

Underneath are the tests for:

Carbonate ions

sulfate ions

chloride ions

bromide ions

iodide ions

Here is summary of “testing for ions” (otherwise known as qualitative analysis). These “tests for ions” are commonly asked in iGCSE Edexcel Chemistry.

Each ionic compound contains positive ions and negative ions. To use the decision tree, start at the top and if a test is negative then move down to the next test.

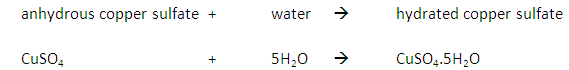

Add anhydrous copper (II) sulfate (CuSO4) to a sample.

If water is present the anhydrous copper (II) sulfate will change from white to blue.

If the sample is pure water it will boil at 100oC

Exothermic: chemical reaction in which heat energy is given out.

Endothermic: chemical reaction in which heat energy is taken in.

(So, in an exothermic reaction the heat exits from the chemicals so temperature rises)

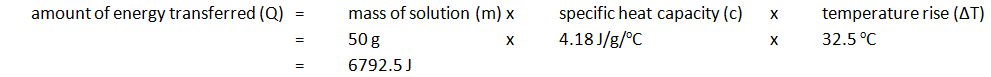

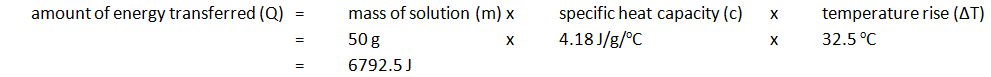

Calorimetry allows for the measurement of the amount of energy transferred in a chemical reaction to be calculated.

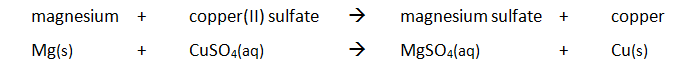

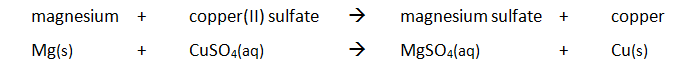

EXPERIMENT1: Displacement, dissolving and neutralisation reactions

Example: magnesium displacing copper from copper(II) sulfate

Method:

| Initial temp. of solution (oC) | Maximium temp. of solution (oC) | Temperature rise (oC) |

|---|---|---|

| 24.2 | 56.7 | 32.5 |

Note: mass of 50 cm3 of solution is 50 g

The cup used is polystyrene because:

polystyrene is an insulator which reduces heats loss

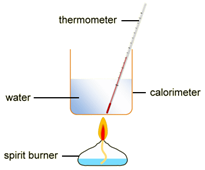

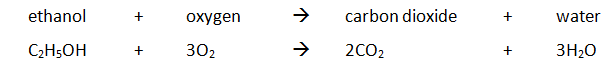

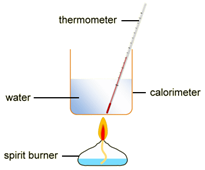

EXPERIMENT2: Combustion reactions

To measure the amount of energy produced when a fuel is burnt, the fuel is burnt and the flame is used to heat up some water in a copper container

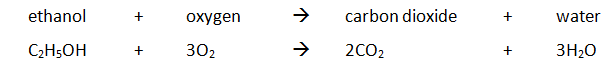

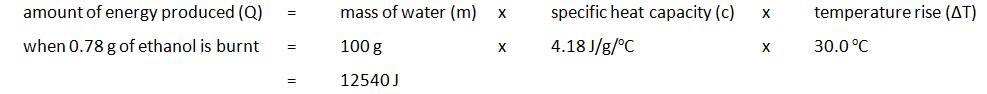

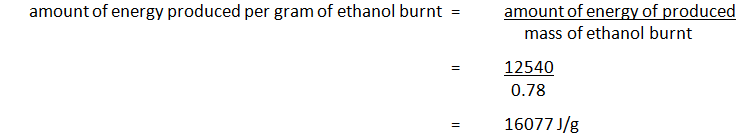

Example: ethanol is burnt in a small spirit burner

Method:

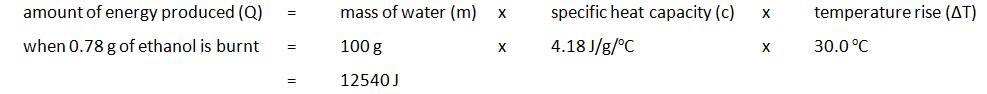

| Mass of water (g) | Initial temp of water (oC) | Maximum temp of water (oC) | Temperature rise (oC) | Initial mass of spirit burner + ethanol (g) | Final mass of spirit burner + ethanol (g) | Mass of ethanol burnt (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 24.2 | 54.2 | 30.0 | 34.46 | 33.68 | 0.78 |

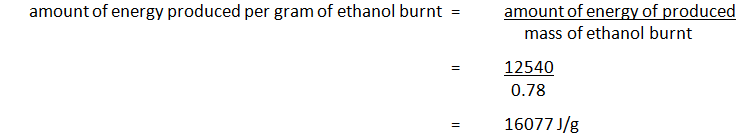

The amount of energy produced per gram of ethanol burnt can also be calculated:

Each type of chemical bond has a particular bond energy. The bond energy can vary slightly depending what compound the bond is in, therefore average bond energies are used to calculate the change in heat (enthalpy change, ΔH) of a reaction.

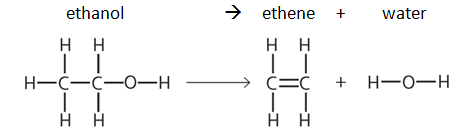

Example: dehydration of ethanol

Note: bond energy tables will always be given in the exam, e.g:

| Bond | Average bond energy in kJ/mol |

|---|---|

| H-C | 412 |

| C-C | 348 |

| O-H | 463 |

| C-O | 360 |

| C=C | 612 |

So the enthalpy change in this example can be calculated as follows:

| Breaking bonds | Making bonds | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Bonds | Energy (kJ/mol) | Bonds | Energy (kJ/mol) |

| H-C x 5 | (412 x 5) = 2060 | C-H x 4 | (412 x 4) = 1648 |

| C-C | 348 | C=C | 612 |

| C-O | 360 | O-H x 2 | (463 x 2) = 926 |

| O-H | 463 | ||

| Energy needed to break all the bonds | 3231 | Energy released to make all the new bonds | 3186 |

Enthalpy change, ΔH = Energy needed to break all the bonds - Energy released to make all the new bonds ΔH = 3231 – 3186 = +45 kJ/mol (ΔH is positive so the reaction is endothermic) |

|||

Here are a couple of videos explaining how to do bond energy calculations:

Calorimetry allows for the measurement of the amount of energy transferred in a chemical reaction to be calculated.

EXPERIMENT1: Displacement, dissolving and neutralisation reactions

Example: magnesium displacing copper from copper(II) sulfate

Method:

| Initial temp. of solution (oC) | Maximium temp. of solution (oC) | Temperature rise (oC) |

|---|---|---|

| 24.2 | 56.7 | 32.5 |

Note: mass of 50 cm3 of solution is 50 g

EXPERIMENT2: Combustion reactions

To measure the amount of energy produced when a fuel is burnt, the fuel is burnt and the flame is used to heat up some water in a copper container

Example: ethanol is burnt in a small spirit burner

Method:

| Mass of water (g) | Initial temp of water (oC) | Maximum temp of water (oC) | Temperature rise (oC) | Initial mass of spirit burner + ethanol (g) | Final mass of spirit burner + ethanol (g) | Mass of ethanol burnt (g) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | 24.2 | 54.2 | 30.0 | 34.46 | 33.68 | 0.78 |

The amount of energy produced per gram of ethanol burnt can also be calculated:

The rate of a chemical reaction can be measured either by how quickly reactants are used up or how quickly the products are formed.

The rate of reaction can be calculated using the following equation:

![]()

The units for rate of reaction will usually be grams per min (g/min)

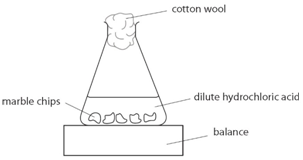

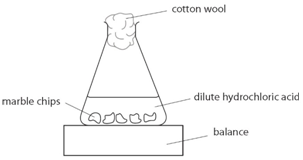

An investigation of the reaction between marble chips and hydrochloric acid:

![]()

Marble chips, calcium carbonate (CaCO3) react with hydrochloric acid (HCl) to produce carbon dioxide gas. Calcium chloride solution is also formed.

Marble chips, calcium carbonate (CaCO3) react with hydrochloric acid (HCl) to produce carbon dioxide gas. Calcium chloride solution is also formed.

Using the apparatus shown the change in mass of carbon dioxide can be measure with time.

As the marble chips react with the acid, carbon dioxide is given off.

The purpose of the cotton wool is to allow carbon dioxide to escape, but to stop any acid from spraying out.

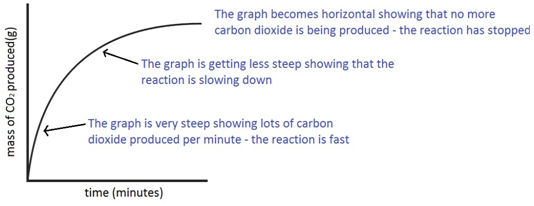

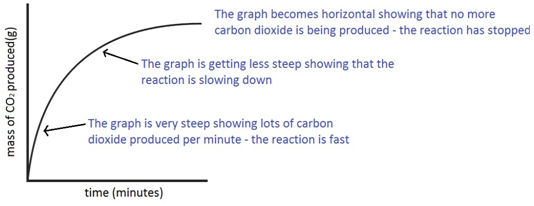

The mass of carbon dioxide lost is measured at intervals, and a graph is plotted:

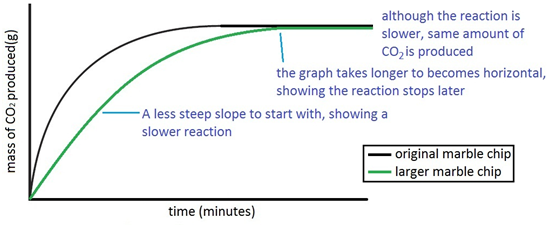

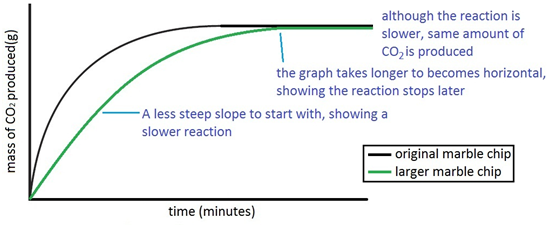

Experiment to investigate the effects of changes in surface area of solid on the rate of a reaction:

The experiment is repeated using the same mass of chips, but this time the chips are larger, i.e. have a smaller surface area.

Since the surface area is smaller, the rate of reaction is less.

Both sets of results are plotted on the same graph.

If instead the chips were smashed into powder (and again same mass of chips used) the surface area would be much larger and so the rate of reaction higher (steeper line on graph).

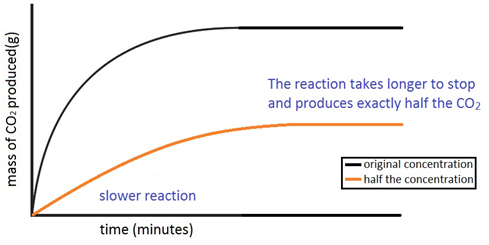

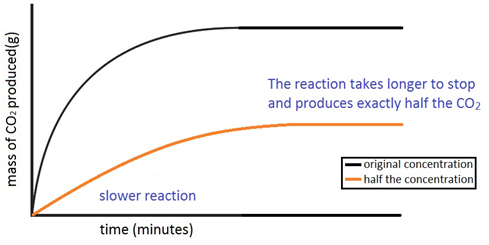

Experiment to investigate the effects of changes in concentration of solutions on the rate of a reaction:

The experiment is again repeated using the exact same quantities of everything but this time with half the concentration of acid. The marble chips must however be in excess. The reaction with the half the concentration of acid happens slower and produces half the amount of carbon dioxide.

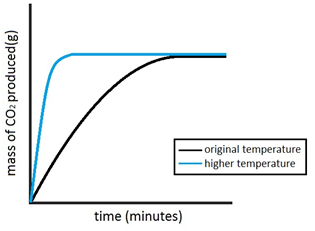

Experiment to investigate the effects of changes in temperature on the rate of a reaction:

The experiment is once again repeated using the exact same quantities of everything but this time at a higher temperature. The reaction with the higher temperature happens faster.

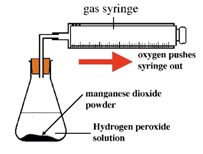

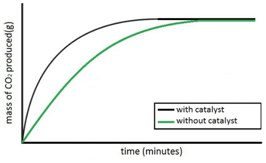

Experiment to investigate the effects of the use of a catalyst on the rate of a reaction:

Hydrogen peroxide naturally decomposes slowly producing water and oxygen gas.

Manganese (IV) oxide can be used as a catalyst to speed up the rate of reaction.

![]()

The rate of reaction can be measured by measuring the volume of oxygen produced at regular intervals using a gas syringe.

Both sets of results are plotted on the same graph.

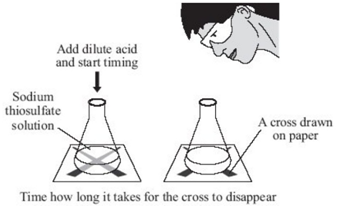

Experiment to investigate the reaction between varying concentrations of sodium thiosulfate and hydrochloric acid

Sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3) and hydrochloric acid (HCl) are both colourless solutions. They react to form a yellow precipitate of sulfur.

sodium thiosulfate + hydrochloric acid → sodium chloride + sulfur dioxide + sulfur + water

Na2S2O3(aq) + 2HCl(aq) → 2NaCl(aq) + SO2(g) + S(s) + H2O(l)

To investigate the effects of changes in concentration of sodium thiosulfate on the rate of a reaction, the conical flask is placed above a cross. The reaction mixture is observed from directly above and the time for a cross to disappear is measured. The cross disappears because a precipitate of sulfur is formed.

In order to change the concentration of sodium thiosulfate, the volumes of sodium thiosulfate and water are varied (see results table). However the total volume of solution must always be kept the same as to ensure that the depth of the solution remains constant.

In this reaction, sulfur dioxide gas (SO2), which is poisonous is produced therefore the experiment must be carried out in a well ventilated room.

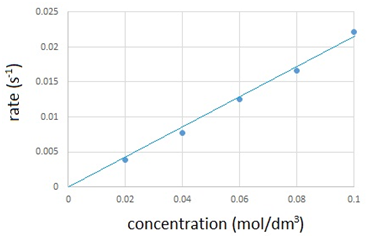

The results are recorded in the table below and then plotted onto a graph.

| Volume of Na2S2O3(aq) (cm3) | Volume of water (cm3) | Concentration of Na2S2O3(aq) (mol/dm3) | Time taken for cross to disappear (s) | Rate of reaction (s-1) (1/time) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50 | 0 | 0.10 | 45 | 0.0222 |

| 40 | 10 | 0.08 | 60 | 0.0167 |

| 30 | 20 | 0.06 | 80 | 0.0125 |

| 20 | 30 | 0.04 | 13 | 0.0769 |

| 10 | 40 | 0.02 | 255 | 0.0039 |

The graph shows that the rate of reaction is directly proportional to the concentration.

The experiment can also be repeated to show how temperature affects the rate of reaction.

In this experiment the concentration of sodium thiosulfate is kept constant but heated to range of different temperatures.

As a rough approximation, the rate of reaction doubles for every 10oC temperature rise.

Increasing the surface area of a solid increases the rate of a reaction.

Increasing the concentration of a solution increases the rate of a reaction.

Increasing the pressure of a gas increases the rate of a reaction.

Increasing the temperature increases the rate of a reaction.

Using a catalyst increases the rate of a reaction.

Increasing the surface area of a solid:

Increasing the concentration of a solution or pressure of a gas:

Increasing the temperature:

A catalyst is a substance that increases the rate of a reaction, but is chemically unchanged at the end of the reaction.

Catalyst: A substance that speeds up a chemical reaction while remaining chemically unchanged at the end of

the reaction.

A catalyst is not used up in a reaction.

A catalyst speeds up a reaction by providing an alternative pathway with lower activation energy.

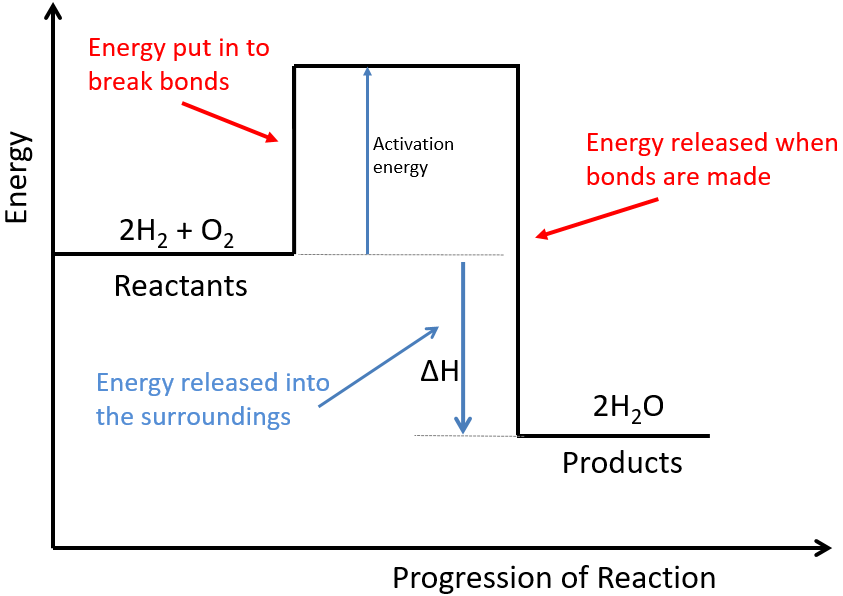

Below is a diagram showing the reaction profile for the reaction of hydrogen with oxygen, which is EXOTHERMIC:

The activation energy is the minimum amount of energy required to start the reaction.

For an exothermic reaction, the products have less energy than the reactants. The difference between these energy levels is ΔH.

For an exothermic reaction, more energy is released when bonds are formed than taken in when bonds are broken.

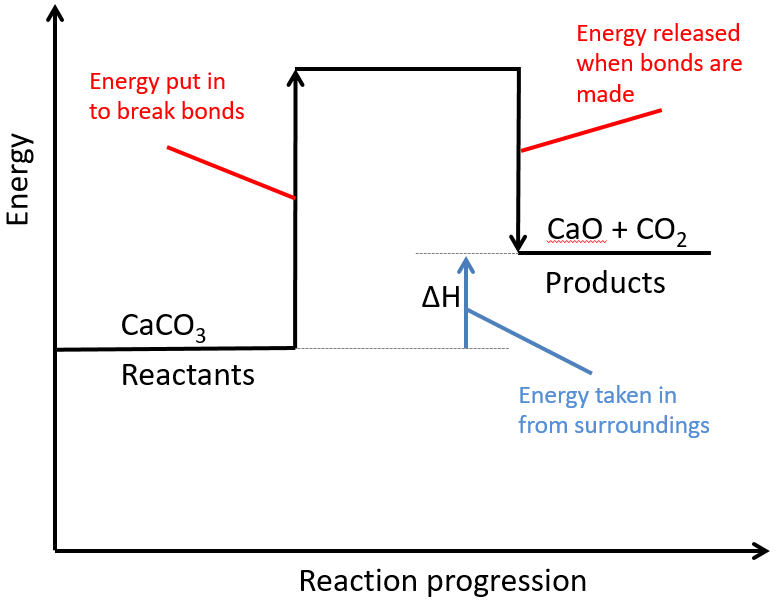

Below is a diagram showing the reaction profile for the thermal decomposition of calcium carbonate, which is ENDOTHERMIC:

The activation energy is the minimum amount of energy required to start the reaction.

For an endothermic reaction, the products have more energy than the reactants. The difference between these energy levels is ΔH.

For an endothermic reaction, more energy is taken in to break bonds than is released when new bonds are formed.

The rate of a chemical reaction can be measured either by how quickly reactants are used up or how quickly the products are formed.

The rate of reaction can be calculated using the following equation:

![]()

The units for rate of reaction will usually be grams per min (g/min)

An investigation of the reaction between marble chips and hydrochloric acid:

![]()

Marble chips, calcium carbonate (CaCO3) react with hydrochloric acid (HCl) to produce carbon dioxide gas. Calcium chloride solution is also formed.

Marble chips, calcium carbonate (CaCO3) react with hydrochloric acid (HCl) to produce carbon dioxide gas. Calcium chloride solution is also formed.

Using the apparatus shown the change in mass of carbon dioxide can be measure with time.

As the marble chips react with the acid, carbon dioxide is given off.

The purpose of the cotton wool is to allow carbon dioxide to escape, but to stop any acid from spraying out.

The mass of carbon dioxide lost is measured at intervals, and a graph is plotted:

Experiment to investigate the effects of changes in surface area of solid on the rate of a reaction:

The experiment is repeated using the exact same quantities of everything but using larger chips. For a given quantity, if the chips are larger then the surface area is lesson. So reaction with the larger chips happens more slowly.

Both sets of results are plotted on the same graph.

Experiment to investigate the effects of changes in concentration of solutions on the rate of a reaction:

The experiment is again repeated using the exact same quantities of everything but this time with half the concentration of acid. The marble chips must however be in excess. The reaction with the half the concentration of acid happens slower and produces half the amount of carbon dioxide.