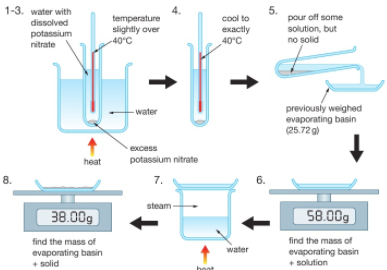

1:07 (Triple only) practical: investigate the solubility of a solid in water at a specific temperature

At a chosen temperature (e.g. 40⁰C) a saturated solution is created of potassium nitrate (KNO₃) for example.

Some of this solution (not any residual solid) is poured off and weighed. The water is then evaporated from this solution to leave a residue of potassium nitrate which is then weighed.

The difference between the two measured masses is the mass of evaporated water.

The solubility, in grams per 100g of water, is equal to 100 times the mass of potassium nitrate residue divided by the mass of evaporated water.

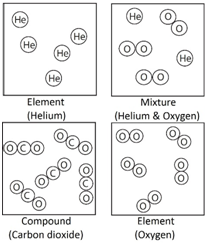

1:08 understand how to classify a substance as an element, a compound or a mixture

Element: The simplest type of substances made up of only one type of atom.

Compound: A substance that contains two or more elements chemically joined together in fixed proportions.

Mixture: Different substances in the same space, but not chemically combined.

Note: elements such as oxygen (O2) are described as diatomic because they contain two atoms.

The full list of elements that are diatomic is:

- Hydrogen (H2)

- Nitrogen (N2)

- Fluorine (F2)

- Oxygen (O2)

- Iodine (I2)

- Chlorine (Cl2)

- Bromine (Br2)

Harry Potter does The Elements – video

Watch Daniel Radcliffe sing the names of all the elements – it’s just a shame there are now more elements than were written into Tom Lehrer’s famous song…..

How do we separate the seemingly inseperable? – video

There are several things in this video which are “beyond the exam spec” but there are loads of interesting bits…..

1:09 understand that a pure substance has a fixed melting and boiling point, but that a mixture may melt or boil over a range of temperatures

Pure substances, such as an element or a compound, melt and boil at fixed temperatures.

However, mixtures melt and boil over a range of temperatures.

Example: although pure water boils at 100⁰C, the addition of 10g of sodium chloride (NaCl) to 1000cm³ of water will raise the boiling point to 100.2⁰C.

Example: although pure water melts at 0⁰C, the addition of 10g of sodium chloride (NaCl) to 1000cm³ of water will lower the melting point to -0.6⁰C.

1:10 describe these experimental techniques for the separation of mixtures: simple distillation, fractional distillation, filtration, crystallisation, paper chromatography

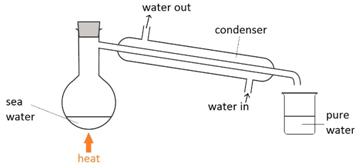

Simple distillation

This method is used to separate a liquid from a solution. For example: separating water from salt water.

The salt water is boiled. The water vapour condenses back into a liquid when passed through the condenser. The salt is left behind in the flask.

Note: cold water is passed into the bottom of the condenser and out through the top so that the condenser completely fills up with water.

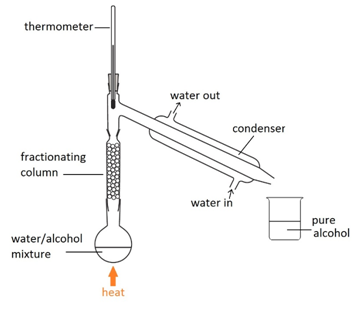

Fractional distillation

This method is used to separate a mixture of different liquids that have different boiling points. For example, separating alcohol from a mixture of alcohol and water.

Water boils at 100oC and alcohol boils at 78oC. By using the thermometer to carefully control of temperature of the column, keeping it at 78oC, only the alcohol remains as vapour all the way up to the top of the column and passes into the condenser.

The alcohol vapours then condense back into a liquid.

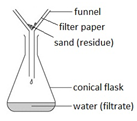

Filtration

Filtration

This method is used to separate an insoluble solid from a liquid. For example: separating sand from a mixture of sand and water.

The mixture is poured into the filter paper. The sand does not pass through and is left behind (residue) but the water passes through the filter paper and is collected in the conical flask (filtrate).

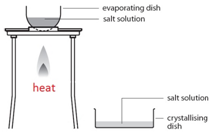

Crystallisation

This method is used to obtain a salt which contains water of crystallisation from a salt solution. For example: hydrated copper sulfate crystals (CuSO4.5H2O(s)) from copper sulfate solution (CuSO4(aq)).

Gently heat the solution in an evaporating basin to evaporate some of the water

Gently heat the solution in an evaporating basin to evaporate some of the water- until crystals form on a glass rod (which shows that a hot saturated solution has formed).

- Leave to cool and crystallise.

- Filter to remove the crystals.

- Dry by leaving in a warm place.

If instead the solution is heated until all the water evaporates, you would produce a powder of anhydrous copper sulfate (CuSO4(s)).

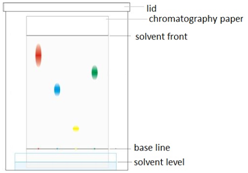

Paper chromatography

This method can be used to separate the parts of a mixture into their components. For example, the different dyes in ink can all be separated and identified.

The coloured mixture to be separated (e.g. a food dye) is dissolved in a solvent like water or ethanol and carefully spotted onto the chromatography paper on the baseline, which is drawn in pencil so it doesn’t ‘run or smudge’.

The paper is carefully dipped into the solvent and suspended so the baseline is above the liquid solvent, otherwise all the spots would dissolve in the solvent. The solvent is absorbed into the paper and rises up it as it soaks into the paper. The choice of solvent depends on the solubility of the dye. If the dye does not dissolve in water then normally an organic solvent (e.g. ethanol) is used.

As the solvent rises up the paper it will carry the dyes with it. Each different dye will move up the paper at different rates depending on how strongly they stick to the paper and how soluble they are in the solvent.

Preparation of CuSO₄ – video

Below is the preparation of copper sulfate crystals (CuSO4.5H2O) through the process of filtration and crystallisation

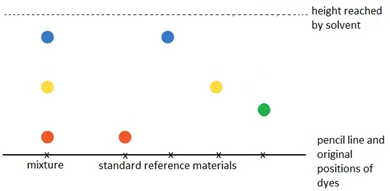

1:11 understand how a chromatogram provides information about the composition of a mixture

Paper chromatography can be used to investigate the composition of a mixture.

A baseline is drawn on the paper. The mixture is spotted onto the baseline alongside known or standard reference materials. The end of the paper is then put into a solvent which runs up the paper and through the spots, taking some or all of the dyes with it.

Different dyes will travel different heights up the paper.

The resulting pattern of dyes is called a chromatogram.

In the example shown, the mixture is shown to contain the red, blue and yellow dyes. This can be seen because these dots which resulted from the mixture have travelled the same distance up the paper as have the red, blue and yellow standard reference materials.

1:12 understand how to use the calculation of Rf values to identify the components of a mixture

When analysing a chromatogram, the mixture being analysed is compared to standard reference materials by measuring how far the various dyes have travelled up the paper from the baseline where they started.

For each dye, the Rf value is calculated. To do this, 2 distances are measured:

- The distance between the baseline and the dye

- The distance between the baseline and the solvent front, which is how far the solvent has travelled from the baseline

The Rf value is calculated as follows:

If the Rf value of one of the components of the mixture equals the Rf value of one of the standard reference materials then that component is know to be that reference material.

Note that because the solvent always travels at least as far as the highest dye, the Rf value is always between 0 and 1.

Dyes which are more soluble will have higher Rf values than less soluble dyes. In other words, more soluble dyes move further up the paper. The extreme case of this is for insoluble dyes which don’t move at all (Rf value = 0). The other aspect affecting how far a dye travels is the affinity that dye has for the paper (how well it ‘sticks’ to the paper).

1:13 practical: investigate paper chromatography using inks/food colourings

- A pencil line (baseline) is drawn 1cm from the bottom of the paper. Pencil will not dissolve in the solvent, but if ink were used instead it might dissolve and interfere with the results of the chromatography.

- A spot of each sample of dye is dropped at different points along the baseline.

- The paper is suspended in a beaker which contains a small amount of solvent. The bottom of the paper should be touching the solvent, but the baseline with the dyes should be above the level of the solvent. This is important so the dyes don’t simply dissolve into the solvent in the beaker.

- A lid should cover the beaker so the atomosphere becomes saturated with the solvent. This is so the solvent does not evaporate from the surface of the paper.

- When the solvent has travelled to near the top of the paper, the paper is removed from the solvent and a pencil line drawn (and labelled) to show the level the solvent reached up the paper. This is called the solvent front.

- The chromatogram is then left to dry so that all the solvent evaporates.

Common solvents are water or ethanol. The choice of solvent depends on whether most of the dyes are soluble in that solvent.

1:14a know what is meant by the terms atom

Atom: An atom is the smallest part of an element.

1:14 know what is meant by the terms atom and molecule

Atom: An atom is the smallest part of an element.

Molecule: A molecule is made of a fixed number of atoms covalently bonded together.

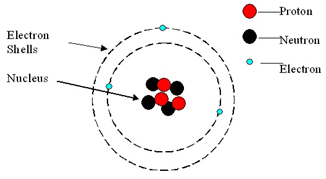

1:15 know the structure of an atom in terms of the positions, relative masses and relative charges of sub-atomic particles

An atom consists of a central nucleus, composed of protons and neutrons.

This is surrounded by electrons, orbiting in shells (energy levels).

Atoms are neutral because the numbers of electrons and protons are equal.

| Mass | Charge | |

|---|---|---|

| Proton | 1 | +1 |

| Neutron | 1 | 0 |

| Electron | negligible (1/1836) | -1 |

Atomic structure – Tyler de Witt video

This video explains the basics of atomic structure, telling you what is inside an atom:

Build an atom – interactive

This is a good interactive demonstration showing how subatomic particles make up the atoms in the Periodic Table.

1:16a know what is meant by the terms atomic number, mass number and relative atomic mass (Aᵣ)

Atomic number: The number of protons in an atom.

Mass number: The number of protons and neutrons in an atom.

Relative atomic mass (Ar): The average mass of an atom compared to 1/12th the mass of carbon-12.

1:16 know what is meant by the terms atomic number, mass number, isotopes and relative atomic mass (Aᵣ)

Atomic number: The number of protons in an atom.

Mass number: The number of protons and neutrons in an atom.

Isotopes: Atoms of the same element (same number of protons) but with a different number of neutrons.

Relative atomic mass (Ar): The average mass of an atom compared to 1/12th the mass of carbon-12.

1:17 be able to calculate the relative atomic mass of an element (Aᵣ) from isotopic abundances

75% of chlorine atoms are the type 35Cl (have a mass number of 35)

25% of chlorine atoms are of the type 37Cl (have a mass number of 37)

In order to calculate the relative atomic mass (Ar) of chlorine, the following steps are used:

- Multiply the mass of each isotope by its relative abundance

- Add those together

- Divide by the sum of the relative abundances (normally 100)

Example question:

A sample of bromine contained the two isotopes in the following proportions: bromine-79 = 50.7% and bromine-81 = 49.3%.

Calculate the relative atomic mass (Ar) of bromine.

Calculation of relative atomic mass – Tyler de Witt video

This excellent video from Tyler de Witt walks you through what isotopes are, and how the relative abundance of those isotopes can be used to calculate the relative atomic mass of an element.

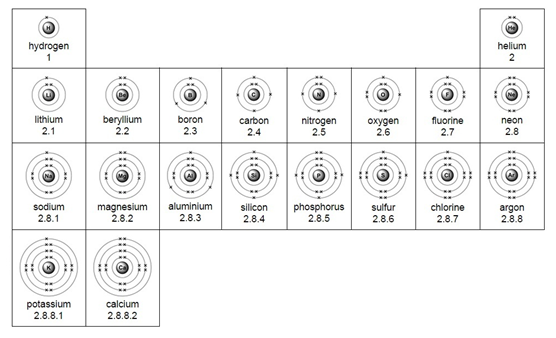

1:18 understand how elements are arranged in the Periodic Table: in order of atomic number, in groups and periods

The elements in the Periodic Table are arranged in order of increasing atomic number.

Columns are called Groups. They indicate the number of electrons in the outer shell of an atom.

Rows are called Periods. They indicate the number of shells (energy levels) in an atom.

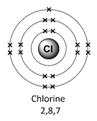

1:19 understand how to deduce the electronic configurations of the first 20 elements from their positions in the Periodic Table

Electrons are found in a series of shells (or energy levels) around the nucleus of an atom.

Each energy level can only hold a certain number of electrons. Low energy levels are always filled up first.

Rules for working out the arrangement (configuration) of electrons:

Example – chlorine (Cl)

1) Use the periodic table to look up the atomic number. Chlorine’s atomic number (number of protons) is 17.

2) Remember the number of protons = number of electrons. Therefore chlorine has 17 electrons.

3) Arrange the electrons in levels (shells):

- 1st shell can hold a maximum of 2

- 2nd can hold a maximum of 8

- 3rd can also hold 8

Therefore the electron arrangement for chlorine (17 electrons in total) will be written as 2,8,7

4) Check to make sure that the electrons add up to the right number

The electron arrangement can also be draw in a diagram.

Electron arrangement for the first 20 elements:

1:20a understand how to use electrical conductivity to classify elements as metals or non-metals

Metals

- conduct electricity

Non – Metals

- do not conduct electricity (except for graphite)

1:20 understand how to use electrical conductivity and the acid-base character of oxides to classify elements as metals or non-metals

Metals

- conduct electricity

- have oxides which are basic, reacting with acids to give a salt and water

Non – Metals

- do not conduct electricity (except for graphite)

- have oxides which are acidic or neutral

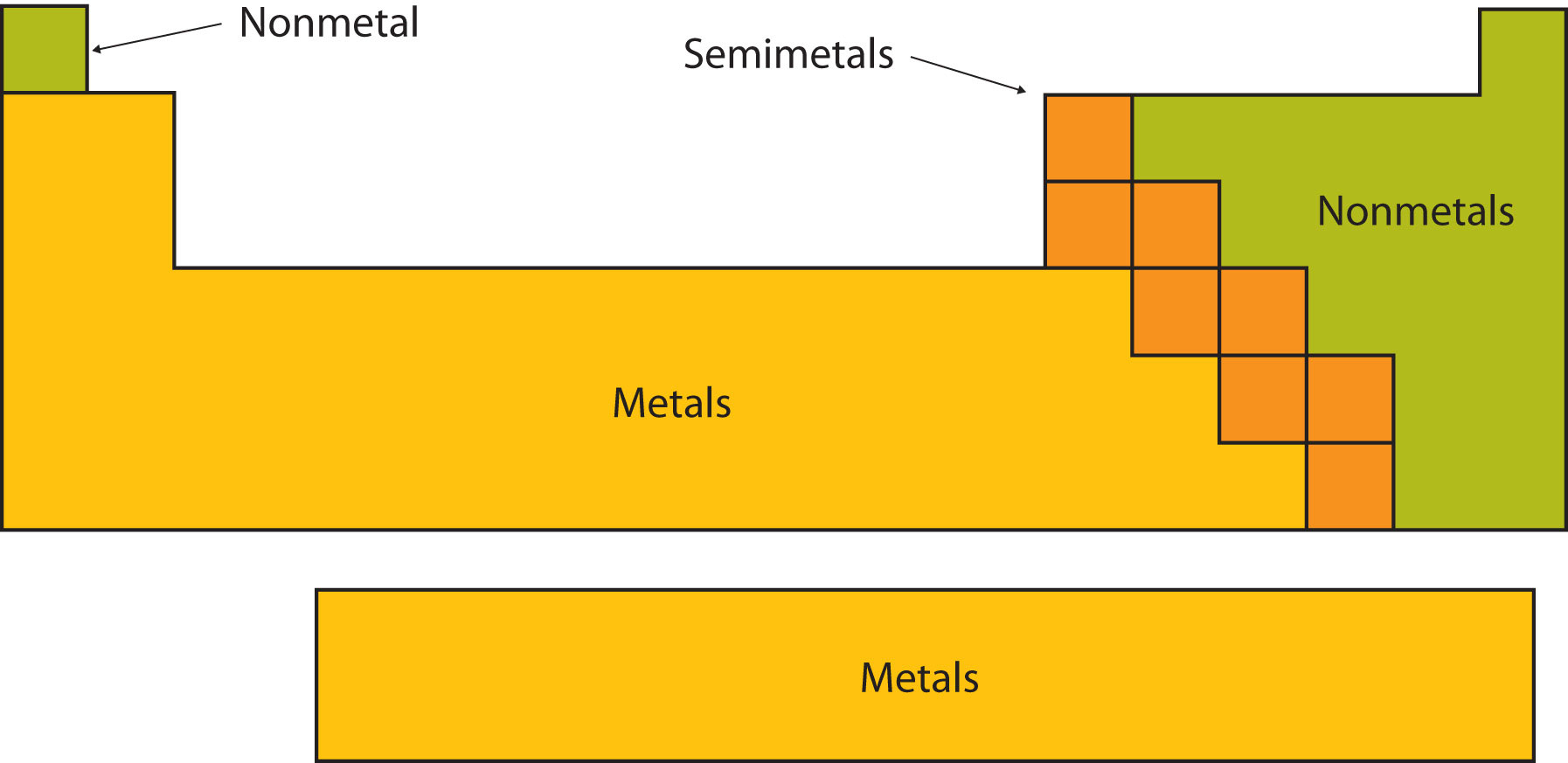

1:21 identify an element as a metal or a non-metal according to its position in the Periodic Table

Metals on the left of the Periodic Table.

Non-Metals on the top-right, plus Hydrogen.

1:22 understand how the electronic configuration of a main group element is related to its position in the Periodic Table

Elements in the same group have the same number of electrons in their outer shell.

This is why elements from the same group have similar properties.

1:23 Understand why elements in the same group of the Periodic Table have similar chemical properties

Elements in the same group of the periodic table have the same number of electrons in their outer shells, which means they have similar chemical properties.

1:24 understand why the noble gases (Group 0) do not readily react

The noble gases are inert (unreactive) because they have a full outer shell of electrons.

1:25 write word equations and balanced chemical equations (including state symbols): for reactions studied in this specification and for unfamiliar reactions where suitable information is provided

Example:

Sodium (Na) reacts with water (H2O) to produce a solution of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and hydrogen gas (H2).

Word equation:

sodium + water –> sodium hydroxide + hydrogen

Writing the chemical equation

A chemical equation represents what happens in terms of atoms in a chemical reaction.

Step 1: To write a chemical equation we need to know the chemical formulae of the substances.

Na + H2O –> NaOH + H2

Step 2: The next step is to balance the equation: write a large number before each compound so the number of atoms of each element on the left hand side (reactants) matches the number on the right (products). This large number is the amount of each compound or element.

During this balancing stage the actual formulas for each compound must not be changed. Only the number of each compound changes.

2Na + 2H2O –> 2NaOH + H2

If asked for an equation, the chemical equation must be given.

State symbols are used to show what physical state the reactants and products are in.

| State symbols | Physical state |

|---|---|

| (s) | Solid |

| (l) | Liquid |

| (g) | Gas |

| (aq) | Aqueous solution (dissolved in water) |

Example:

A solid piece of sodium (Na) reacts with water (H2O) to produce a solution of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) and hydrogen gas (H2).

2Na(s) + 2H2O(l) –> 2NaOH(aq) + H2(g)

Balancing equations – Tyler de Witt videos

This excellent Tyler de Witt video is an introduction to balancing equations:

And here’s another of the lovely Tyler’s videos with some practice questions and answers on equation balancing:

Balancing equations – interactive

This is useful to help you to practice how to balance equations:

1:26 calculate relative formula masses (including relative molecular masses) (Mᵣ) from relative atomic masses (Aᵣ)

Relative formula mass (Mr) is mass of a molecule or compound (on a scale compared to carbon-12).

It is calculated by adding up the relative atomic masses (Ar) of all the atoms present in the formula.

Example:

The relative formula mass (Mr) for water (H2O) is 18.

Water = H2O

Atoms present = (2 x H) + (1 x O)

Mr = (2 x 1) + (1 x 16) = 18

Calculation of relative formula mass – Tyler de Witt video

Here’s an excellent Tyler de Witt video explaining how to calculate the relative formula mass of compounds with:

- a simple formula

- a formula which includes brackets

- a formula which includes a dot (water of crystallisation)

1:27 know that the mole (mol) is the unit for the amount of a substance

In Chemistry, the mole is a measure of amount of substance (n).

The abbreviation for mole is mol.

The mass of 1 mole of a substance is the relative formula mass (Mr) of the substance in grams.

Example:

The Mr of water is 18.

Therefore the mass of 1 mol of water equals 18 g.

1:28 understand how to carry out calculations involving amount of substance, relative atomic mass (Aᵣ) and relative formula mass (Mᵣ)

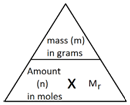

The following formula allows for the interconversion between a mass in grams and a number of moles for a given substance:

Example 1:

Calculate the amount, in moles, of 8.8 g of carbon dioxide (CO2).

Step 1: Calculate the relative formula mass (Mr) of carbon dioxide (CO2).

Step 2: Use the formula to calculate the amount in moles.

Example 2:

Calculate the mass of 2 mol of copper(II) sulfate (CuSO4).

Step 1: Calculate the relative formula mass (Mr) of copper(II) sulfate (CuSO4).

Step 2: Rearrange the formula to calculate the mass.

Calculations involving mass (in grams), amount (in moles) and relative atomic mass – Tyler de Witt video

This video shows how to perform calculations involving mass (in grams), amount (in moles) and relative atomic mass:

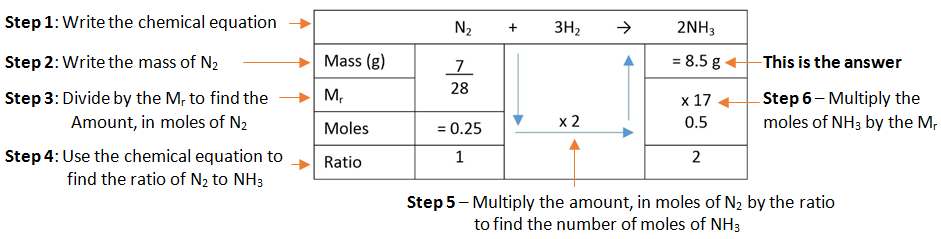

1:29 calculate reacting masses using experimental data and chemical equations

Example: When calcium carbonate (CaCO3) is heated calcium oxide is produced. You can use reacting mass calculations to calculate the mass of calcium oxide produced when heating 25 g of calcium carbonate.

CaCO3 –> CaO + CO2

Step 1: Calculate the amount, in moles, of 25 g of calcium carbonate (CaCO3)

Step 2: Deduce the amount, in moles, of CaO produced from 0.25 mol of CaCO3.

This step involves using the ratio of CaCO3 to CaO from the chemical equation.

CaCO3 –> CaO + CO2

From the equation you can see that the ratio of CaCO3 to CaO is 1:1.

Therefore if you have 0.25 mol of CaCO3 this will produced 0.25 mol of CaO.

Step 3: Calculate the mass of 0.25 mol of CaO.

A simple format for laying out this method can be used.

Example: What mass of ammonia (NH3) is formed when 7 g of nitrogen (N2) is combined with hydrogen (H2).

Calculate Reacting Masses video

This video steps through a very useful method used to calculate reacting masses.

1:30 calculate percentage yield

Yield is how much product you get from a chemical reaction.

The theoretical yield is the amount of product that you would expect to get. This is calculated using reacting mass calculations.

In most chemical reactions, however, you rarely achieved your theoretical yield.

For example, in the following reaction:

CaCO3 –> CaO + CO2

You might expect to achieve a theoretical yield of 56 g of CaO from 100 g of CaCO3.

However, what if the actual yield is only 48 g of CaO.

By using the following formula, the % yield can be calculated:

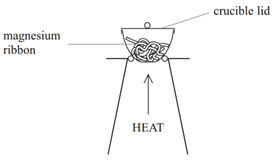

1:31a understand how the formulae of simple compounds can be obtained experimentally, including metal oxides

Finding the formula of a metal oxide experimentally

The formulae of metal oxides can be found experimentally by reacting a metal with oxygen and recording the mass changes.

Example: When magnesium is burned in air, it reacts with oxygen (O2) to form magnesium oxide (MgO).

Method:

• Weigh a crucible and lid

• Place the magnesium ribbon in the crucible, replace the lid, and reweigh

• Calculate the mass of magnesium

(mass of crucible + lid + Magnesium – mass of crucible + lid)

• Heat the crucible with lid on until the magnesium burns

(lid prevents magnesium oxide escaping therefore ensuring accurate results)

• Lift the lid from time to time (this allows air to enter)

• Stop heating when there is no sign of further reaction

(this ensures all Mg has reacted)

• Allow to cool and reweigh

• Repeat the heating , cooling and reweigh until two consecutive masses are the same

(this ensures all Mg has reacted and therefore the results will be accurate)

• Calculate the mass of magnesium oxide formed (mass of crucible + lid + Magnesium oxide – mass of crucible + lid)

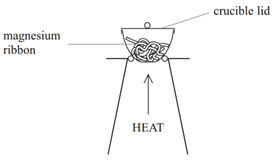

1:31 understand how the formulae of simple compounds can be obtained experimentally, including metal oxides, water and salts containing water of crystallisation

Finding the formula of a metal oxide experimentally

The formulae of metal oxides can be found experimentally by reacting a metal with oxygen and recording the mass changes.

Example: When magnesium is burned in air, it reacts with oxygen (O2) to form magnesium oxide (MgO).

Method:

• Weigh a crucible and lid

• Place the magnesium ribbon in the crucible, replace the lid, and reweigh

• Calculate the mass of magnesium

(mass of crucible + lid + Magnesium – mass of crucible + lid)

• Heat the crucible with lid on until the magnesium burns

(lid prevents magnesium oxide escaping therefore ensuring accurate results)

• Lift the lid from time to time (this allows air to enter)

• Stop heating when there is no sign of further reaction

(this ensures all Mg has reacted)

• Allow to cool and reweigh

• Repeat the heating , cooling and reweigh until two consecutive masses are the same

(this ensures all Mg has reacted and therefore the results will be accurate)

• Calculate the mass of magnesium oxide formed (mass of crucible + lid + Magnesium oxide – mass of crucible + lid)

Finding the formula of a salt containing water of crystallisation

When some substances crystallise from solution, water becomes chemically bound up with the salt. This is called water of crystallisation and the salt is said to be hydrated. For example, hydrated copper sulfate has the formula CuSO4.5H2O which formula indicates that for every CuSO4 in a crystal there are five water (H2O) molecules.

When you heat a salt that contains water of crystallisation, the water is driven off leaving the anhydrous (without water) salt behind. If the hydrated copper sulfate (CuSO4.5H2O) are strongly heated in a crucible then they will break down and the water lost, leaving behind anhydrous copper sulfate (CuSO4). The method followed is similar to that for metal oxides, as shown above. The difference of mass before and after heating is the mass of the water lost. These mass numbers can be used to obtain the formula of the salt.